Once the Labour Party was characterised by tolerance and inclusion, all working class organisations were welcome – no longer. James Marshall of Labour Party Marxists explores the history.

We in the Labour Party are in the midst of a terrible purge. Four examples.

- Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union general secretary Ronnie Draper has been suspended from membership and thereby prevented from voting in the Labour leadership election. Why? An unidentified tweet.

- Tony Greenstein is likewise suspended. A well known Jewish anti-Zionist, he faces baseless charges of being an anti-Semite. His real crime is to oppose the state of Israel … and Labour’s pro-Zionist right wing.

- Then there is Jill Mountford, an executive member of Momentum. She has been expelled. Once again, why? Six years ago, in the May 2010 general election, the comrade stood for the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty against Harriet Harman. A protest against the acceptance of Con-Dem austerity politics, albeit based on a stupid dismissal of the Labour Party as virtually indistinguishable from the US Democrats. However, since then comrade Mountford vows she has supported only Labour candidates.

- Perhaps the most ridiculous disciplinary case is Catherine Starr’s. Having shared a video clip of Dave Grohl’s band she ecstatically wrote: “I fucking love the Foo Fighters”. The thought police nabbed her under the ban on “racist, abusive or foul language, abuse against women, homophobia or anti-Semitism at meetings, on social media or in any other context.”1 Yes, using the word “fucking” in any context, can, nowadays be deemed a breach of the Labour Party’s norms of behaviour.

Unsurprisingly then, there are thousands of Drapers, Greensteins, Mountfords and Starrs. And it is clear what general secretary Iain McNicol, the compliance unit and the Labour right are up to. Create a climate where almost any leftwing public statement, past action or use of unofficial English can be branded as unacceptable, as threatening, as violating the Blairite ‘safe spaces’ policy. Then bar, ban and banish the maximum number of Jeremy Corbyn supporters. Swing things in favour of Owen Smith. True, the right’s chances of success are remote. The odds against citizen Smith are far too great. Nonetheless, this is clearly what the purge is all about.

Meanwhile, despite his massive £2.1 million donation to the Liberal Democrats in June, Lord David Sainsbury, a minister under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, is, at least as things stand today, free to vote in the leadership election. Nor are former Tory or Ukip members suspended or expelled. That despite their undisputed past support for non-Labour candidates. And, of course, there are those MPs who have been throwing one lying accusation after another against the left. They are Nazi stormtroopers. They are anti-Semites. They are Trot infiltrators.

The same MPs have attempted to undermine Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership at every turn. Now, having failed with the anti-Semitism campaign, they are furiously using the capitalist media to spread rumours of an imminent split and getting hold of the Labour Party’s name, offices and assets through the courts. They have gone untouched. A crime in itself.

Unlike John McDonnell we do not complain of “double standards”. We in Labour Party Marxists forthrightly oppose the suspension and expulsion of socialists, leftwingers, working class partisans. All of them, without exception, ought to be immediately reinstated. Whatever our criticisms they are assets who should be valued. It is the treacherous right, the splitters, who deserve to be purged.

There is surely nothing uncontroversial about a Marxist making such a case. After all, the ongoing civil war in the Labour Party is a concentrated manifestation of the struggle of class against class. Labour’s much expanded base faces an onslaught by the pro-capitalist apparatus of Brewer’s Green bureaucrats, MPs, MEPs, councillors, etc. Under such circumstances we Marxists are obliged to actively take sides.

What then should we make of Robert Griffiths, general secretary of the Morning Star’s Communist Party of Britain? He grovellingly wrote to Iain McNicol to assure him that the CPB “does not engage in entryism”. More than that, comrade Griffiths parades his spinelessness:

According to reports in The Guardian and other media outlets … Labour Party staff have produced a research paper [that] links the Communist Party to ‘entryism’ in the Labour Party. In particular, that research paper cites a report made to our party’s executive committee [that] on June 25 declared that “defending the socialist leadership of the Labour Party at all costs” should be a priority for communists. Nowhere in that executive committee report … do we propose that our members join or register with the Labour Party. “At all costs” is a rhetorical flourish that cannot, obviously, be taken literally!

So the CPB should not be taken at its word. It will not defend the Corbyn leadership “at all costs”. And, prostrating himself still further before the witch-finder general, Griffiths continues:

Should you or your staff have any evidence that Communist Party members have joined the Labour Party without renouncing their CP membership, or engaged in any similar subterfuge, please inform me, so that action can be taken against them for bringing our party into disrepute.

Let us be clear about what is being said here: in the middle of a brutal civil war, with the Labour left facing a concerted witch-hunt, the CPB’s Robert Griffiths wants to be seen as standing shoulder to shoulder with Iain McNicol. He even offers to help McNicol out in hunting down any CPB member who has decided to become a registered Labour Party supporter. To my personal knowledge there are more than a few of them. Anyway, not to leave a shadow of doubt, Griffiths signs off “With comradely regards”. A giveaway as to where his true loyalties really lie.

Following Tom Watson’s dodgy dossier, alleging that “far-left infiltrators are taking over the Labour Party”, Griffiths issued a follow-up statement. Again this excuse for a communist leader reassures McNicol that membership of his CPB is “incompatible with membership of the Labour Party by decision of both party leaderships”.

Origins

How exactly Griffiths’ organisation arrived at its ban on Labour Party members joining the CPB and the ban on CPB members joining the Labour Party need not concern us here. Presumably its roots lie in the constitutionalism embraced by the ‘official’ CPGB with its turn to the cross-class politics of the popular front. This was sanctioned by the 5th Congress of the Communist International in 1935 under Stalin’s direct instructions.

Yet the CPB claims to be the unbroken continuation of the ‘official’ CPGB, going back to its foundation in 1920. Nonetheless, as we shall show, it is clear that that a fundamental break occurred. No less importantly, the same can be said of the Labour Party.

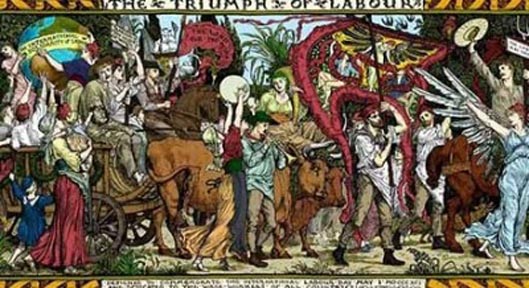

From its origins our Labour Party was a federal party. A united front of all working class organisations with, yes, especially at first, decidedly limited objectives.

JH Holmes, delegate of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, moved this truly historic resolution at the 1899 TUC:

That this Congress, having regard to its decisions in former years, and with a view to securing better representation of the interests of Labour in the House of Commons, hereby instructs the Parliamentary Committee to invite the cooperation of all cooperative, socialistic, trade unions and other working class organisations to jointly cooperate on lines mutually agreed upon, in convening a special congress of representatives from such above-named organisations as may be willing to take part to devise ways and means of securing the return of an increased number of Labour members in the next parliament.

His resolution was opposed by the miners’ union on the basis of impracticability, but found support from the dockers, the railway servants and shop assistants unions. After a long debate the resolution was narrowly carried by 546,000 to 434,000 votes.

The TUC’s parliamentary committee oversaw the founding conference of the Labour Representation Committee in February 1900. The 129 delegates, representing 500,000 members, finally agreed to establish a distinct Labour Party in parliament, with its own whips, policies, finances, etc.

An executive committee was also elected. It would prepare lists of candidates, administer funds and convene an annual conference. Beside representatives of affiliated trade unions, the newly formed NEC would also include the socialist societies: the Fabians, the Independent Labour Party and the Social Democratic Federation. In fact, they were allocated five out of the 12 NEC seats (one Fabian, and two each from the ILP and SDF). Given the small size of these socialist societies compared with the trade unions, it is obvious that they were treated with extreme generosity. Presumably their “advanced” views were highly regarded.

True, for the likes of Keir Hardie the formation of the Labour Party marked something of a tactical retreat. He had long sought some kind of a socialist party. However, to secure an alliance with the trade unions he and other ILPers were prepared to formally limit the Labour Party to nothing more than furthering working class interests by getting “men sympathetic with the aims and demands of the labour movement” into the House of Commons.

The delegates of the SDF proposed that the newly established Labour Party commit itself to the “class war and having as its ultimate object the socialisation of the means of production and exchange” – a formulation rejected by a large majority. In the main the trade unions were still Liberal politically. Unfortunately, as a result of this vote, the next annual conference of the SDF voted by 54 to 14 to withdraw from the Labour Party. Many SDF leaders came to bitterly “regret the decision”.

It should be recalled that neither Marx nor Engels had much time for the SDF nor its autocratic leader, Henry Hyndman. The SDF often took a badly conceived sectarian approach. Instead of linking up with the trade unions, it would typically stand aloof. Eg, faced with the great industrial unrest of 1910-14, Hyndman rhetorically asked: “Can anything be imagined more foolish, more harmful, more – in the widest sense of the word – unsocial than a strike?” Of course, it is quite possible to actively support trade unions in their struggles over wages, conditions, etc, and to patiently and steadfastly advocate radical democracy and international socialism. Indeed without doing just that there can be no hope for a mass socialist party here in Britain.

However, the SDF is too often casually dismissed by historians. Eg, Henry Pelling describes it as “a rather weedy growth in the political garden”. True, its Marxism was typically lifeless, dogmatic and with Hyndman mixed with more than a tinge of anti-Semitism. Thus for him the Boer war was instigated by “Jew financial cliques and their hangers on”. Yet the SDF was “the first modern socialist organisation of national importance” in Britain. Karl Marx disliked it, Fredrick Engels despaired of it, William Morris, John Burns, Tom Mann and Edward Aveling left it. But the SDF survived. There were various breakaways. However, they either disappeared like the Socialist League, remained impotent sects like the Socialist Party of Great Britain, or could manage little more than establishing a regional influence, as with the Socialist Labour Party on Clydeside. Meanwhile the SDF continued as the “major representative” of what passed for Marxism in this country till 1911, when it merged with a range of local socialist societies to become the British Socialist Party.

Not that sectarianism was entirely vanquished. The first conference of the BSP voted, by an overwhelming majority, to “seek direct and independent affiliation” to the Second International. In other words, not through the Labour Party-dominated British section of the Second International.

However, despite that, the BSP began to overcome its Labour-phobia. Leading figures such as Henry Hyndman, J Hunter Watts and Dan Irving eventually came out in favour of affiliation. So too did Zelda Kahan for the left. Withdrawal from the Labour Party, she argued, had been a mistake. Outside the Labour Party the BSP was seen as hostile, as fault-finding, as antagonistic. Inside, the BSP would get a wider hearing and win over the “best” rank-and-file forces.

Affiliation was agreed, albeit by a relatively narrow majority. Efforts then began to put this into effect. The formal application for affiliation was submitted in June 1914. And in 1916 – things having been considerably delayed by the outbreak of World War I – the BSP gained affiliation to the Labour Party. Note, the BSP also in effect expelled the pro-war right wing led by Hyndman.

Labour debates

Interestingly, the International Socialist Bureau – the Brussels-based permanent executive of the Second International – meeting in October 1908, had agreed to Labour Party affiliation … and thus, given its numbers, ensured its domination of the British section. For our present purposes the exchanges between the dozen or so national party representatives gathered in Brussels are well worth revisiting.

According to the rules of the Second International, there could only be two types of affiliate organisations. Firstly, socialist parties “which recognise the class struggle”. Secondly, working class organisations “whose standpoint is that of the class struggle” (ie, trade unions).

During these times the Labour Party positively avoided calling itself socialist. Nor, as we have seen, did it expressly recognise the principle of the class struggle. However, despite that, the Labour Party was admitted to the August 1907 Stuttgart congress of the International. My guess would be that it had observer status. Why was it admitted? Lenin characterised the Labour Party as an “organisation of a mixed type”, standing between the two types defined in the rules. In other words, the Labour Party was part political party, part a political expression of the trade unions. Crucially, the Labour Party marked the break from Liberalism of the vitally important working class in Britain. That could only but be welcomed.

At the October 1908 meeting of the ISB, Bruce Glasier of the ILP demanded the direct recognition of the Labour Party as an affiliate. He praised the Labour Party, its growth, its parliamentary group, its organic bonds with the trade unions, etc. Objectively, he said, this signified the movement of the working class in Britain towards socialism. Meanwhile, as a typical opportunist, Glasier lambasted doctrinaire principles, formulas and catechisms.

Karl Kautsky, the Second International’s leading theoretician, replied. Kautsky emphatically dissociated himself from Glasier’s obvious contempt for principles, but wholly supported the affiliation of the Labour Party, as a party waging the class struggle in practice. He moved the following resolution:

Whereas by previous resolutions of the international congresses all organisations adopting the standpoint of the proletarian class struggle and recognising the necessity for political action have been accepted for membership, the International Bureau declares that the British Labour Party is admitted to International Socialist congresses, because, while not expressly accepting the proletarian class struggle, in practice the Labour Party conducts this struggle, and adopts its standpoint, inasmuch as the party is organised independently of the bourgeois parties.

Kautsky was backed up by the Austrians, Édouard Vaillant of the French section, and, as the voting showed, the majority of the socialist parties and groups in the smaller European countries. Opposition came first from Henry Hyndman, representing the SDF. He wanted to maintain the status quo. Until the Labour Party expressly recognised the principle of the class struggle and the aim of socialism it should not be an affiliate. He found support from Angele Roussel (the second French delegate and a follower of Jules Guesde), Ilya Rubanovich of Russia’s Socialist Revolutionary Party and Roumen Avramov, delegate of the revolutionary wing of the Bulgarian social democrats.

Lenin spoke on behalf of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He agreed with the first part of Kautsky’s resolution. Lenin argued that it was impossible to turn down the Labour Party: ie, what he called “the parliamentary representation of the trade unions”. After all, the ISB admitted trade unions, including those which had allowed themselves to be represented by bourgeois parliamentarians. But, said Lenin, “the second part of Kautsky’s resolution is wrong, because in practice the Labour Party is not a party really independent of the Liberals, and does not pursue a fully independent class policy”. Lenin therefore proposed an amendment that the end of the resolution, beginning with the word “because”, should read as follows: “because it [the Labour Party] represents the first step on the part of the really proletarian organisations of Britain towards a conscious class policy and towards a socialist workers’ party”.

However, Kautsky refused to accept the amendment. In his reply, he argued that the International Socialist Bureau could not adopt decisions based on “expectations”.

But the main struggle was between the supporters and the opponents of Kautsky’s resolution as a whole. When it was about to be voted on, Victor Adler, the Austro-Marxist, proposed that the resolution be divided into two parts. This was done and both parts were carried by the ISB: the first with three against and one abstention, and the second with four against and one abstention. Thus Kautsky’s resolution became the agreed position. Rubanovich, the Socialist Revolutionary, abstained on both votes. Lenin also reports what Adler – who spoke after him but before Kautsky’s second speech – said: “Lenin’s proposal is tempting, but it cannot make us forget that the Labour Party is now outside the bourgeois parties. It is not for us to judge how it did this. We recognise the fact of progress.”

The ISB dispute over the Labour Party continued in the socialist press. Fending off charges of “heresy” from leftist critics, Kautsky elaborated his ideas in a 1909 Neue Zeitarticle, ‘Sects or class parties’. Basically he argued that, unlike Germany and other mainland European countries, a mass workers’ party in Britain is impossible without linking up with the trade unions. Unless that happened, there could be nothing but sects and small circles.

In the Labour Leader, the ILP’s paper, Bruce Glasier rejoiced that the ISB not only recognised the Labour Party (which was true), but also “vindicated the policy of the ILP” (which was not true). Another ILPer, giving his impression of the Brussels meeting of the ISB, complained about the absence of the “ideal and ethical aspect of socialism”. Instead we “had … the barren and uninspiring dogma of the class war”.

As for Hyndman, writing in the SDF’s Justice, he expressed his anger at the ISB majority. They are “whittlers-away of principle to suit the convenience of trimmers”. “I have not the slightest doubt,” writes Hyndman, “that if the British Labour Party had been told plainly that they either had to accept socialist principles … or keep away altogether, they would very quickly have decided to bring themselves into line with the International Socialist Party.”

Lenin too joined the fray. He still considered Kautsky to be wrong. By stating in his resolution that the Labour Party “does not expressly accept the proletarian class struggle”, Kautsky voiced a certain “expectation”, a certain “judgement” as to what the policy of the Labour Party is now and what that policy should be. But Kautsky expressed this indirectly, and in such a way that it amounted to an assertion which, first, is incorrect in substance, and secondly, provides a basis for opportunists in the ILP to misrepresent his ideas.

By separating in parliament (but not in terms of its whole policy) from the two bourgeois parties, the Labour Party is “taking the first step towards socialism and towards a class policy of the proletarian mass organisations”. This, Lenin optimistically stated, is not an “expectation, but a fact”. A “fact” which compelled the ISB to admit the Labour Party into the International. Putting things this way, Lenin thought, “would make hundreds of thousands of British workers, who undoubtedly respect the decisions of the International, but have not yet become full socialists, ponder once again over the question why they are regarded as having taken only the first step, and what the next steps along this road should be”.

Lenin had no intention of laying down details about those “next steps”. But they were necessary, as Kautsky acknowledged in his resolution, albeit only indirectly. However, the use of an indirect formulation made it appear that the International was “certifying that the Labour Party was in practice waging a consistent class struggle, as if it was sufficient for a workers’ organisation to form a separate labour group in parliament in order in its entire conduct to become independent of the bourgeoisie!”

The International, Lenin concluded, would undoubtedly have acted wrongly had it not expressed its complete support for the vital first step forward taken by the mass of workers in forming the Labour Party. But it does not in the least follow from this that the Labour Party “can already be recognised as a party in practice independent of the bourgeoisie, as a party waging the class struggle, as a socialist party, etc”.

Bolshevism

The October revolution in Russia found unanimous and unstinting support in the BSP. A number of its émigré comrades returned home and took up important roles in the Soviet government. Bolshevik publications were soon being translated into English: eg, Lenin’s State and revolution. Money too flowed in.

The Leeds conference of the BSP in 1918 enthusiastically declared its solidarity with the Bolsheviks and a wish to emulate their methods and achievements. And under the influence of the Bolsheviks the BSP adopted a much more active, much more agitational role in the Labour Party and the trade unions. In the words of Fred Shaw, instead of standing aloof from the “existing organisations” of the working class, we should “win them for Marxism”.

Needless to say, the BSP constituted the main body that went towards the historic formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain over July 31-August 1 1920. Given BSP affiliation, and the fact that in 1918 the Labour Party introduced individual membership, there can be no doubt that the bulk of CPGBers were card-carrying members of the Labour Party. Dual membership being the norm, as it was in the Fabians and ILP.

However, instead of simply informing Arthur Henderson, the Labour Party’s secretary, that the BSP had changed its name, the CPGB, following Lenin’s advice, applied for affiliation. Lenin thought the CPGB was in a win-win situation. If affiliation was accepted, this would open up the Labour Party rank and file to communist influence. If affiliation was not accepted, this would expose the Labour leaders for what they really were: namely “reactionaries of the worst kind”.

With 20:20 foresight it would probably have been better for the CPGB to have presented itself merely as the continuation of the BSP. After all, gaining a divorce is far harder than turning down a would-be suitor. Needless to say, upholding its commitment to British imperialism and thereby fearing association with the Bolshevik revolution, the Labour apparatus, along with the trade union bureaucracy, determined that the CPGB application had to be rejected.

The “first step towards socialism and towards a class policy” was thereby thrown into reverse. Instead of being a united front of the organised working class, the leadership of the Labour Party began to cohere a tightly controlled, thoroughly respectable, explicitly anti-Marxist Labour Party.

Henderson replied to the CPGB application for affiliation by saying that he did not consider that the principles of the communists accorded with those of the Labour Party. To which the CPGB responded by asking whether the Labour Party proposed to “exclude from its ranks” all those who were committed to the “political, social and economic emancipation of the working class”. Did Henderson want to “impose acceptance of parliamentary constitutionalism as an article of faith on its affiliated societies”? The latter bluntly replied that there was an “insuperable difference” between the two parties.

A good many Labour Party activists rejected Henderson’s characterisation of the CPGB as, in effect, mad, bad and dangerous to know. Nonetheless, the Labour apparatus never experienced any difficulty in mustering large majorities against CPGB affiliation. Eg, in June 1921 there was a 4,115,000 to 224,000 conference vote rejecting the CPGB.

Not that the CPGB limped on as an isolated sect. Affiliation might have been rejected, but there was still dual membership. In 1922, two CPGB members won parliamentary seats as Labour candidates: JT Walton Newbold (Motherwell and Wishaw) and Shapurji Saklatvala (Battersea North).

Subsequently, Labour’s national executive committee was forced to temporarily drop its attempt to prevent CPGB members from being elected as annual conference delegates. The June 26-29 1923 London conference had 36 CPGB members as delegates, “as against six at Edinburgh”, the previous year. Incidentally, the 1923 conference once again rejected CPGB affiliation, this time by 2,880,000 to 366,000 votes.

Nonetheless, the general election in December 1923 saw Walton Newbold (Motherwell) and Willie Gallacher (Dundee) standing as CPGB candidates. Fellow CPGBers Ellen Wilkinson (Ashton-under-Lyne), Shapurji Saklatvala (Battersea North), M Philips Price (Gloucester), William Paul (Manchester Rusholme) and Joe Vaughan (Bethnal Green SW) were official Labour candidates, while Alec Geddes (Greenock) and Aitkin Ferguson (Glasgow Kelvingrove) were unofficial Labour candidates, there being no official Labour candidate in either constituency. Despite a not inconsiderable increase in the communist vote, none were elected.

A ban on CPGB members standing as Labour Party candidates swiftly followed. Yet, although Labour Party organisations were instructed not to support CPGB candidates, this was met with defiance, not the connivance nowadays personified by Robert Griffiths. In the run-up to the October 1924 general election, Battersea North Labour Party overwhelmingly endorsed Shapurji Saklatvala; Joe Vaughan was unanimously endorsed by Bethnal Green SW Constituency Labour Party and William Paul similarly by the Rusholme CLP executive committee. And Saklatvala was once again elected as an MP.

The 1924 Labour Party conference decision against CPGB members continuing with dual membership was reaffirmed in 1925. And, going further, trade unions were “asked not to nominate communists as delegates to Labour organisations”. Yet despite these assaults on the Labour Party’s founding principles, at the end of 1926 the CPGB could report that 1,544 of its 7,900 members were still individual members of the Labour Party.

Following the defeat of the 1926 General Strike, the Labour apparatus and trade union bureaucracy wanted the movement to draw the lesson that the only way to make gains would be through increased collaboration with the capitalist boss class – Mondism. As a concomitant there was a renewed drive to intimidate, to marginalise, to drive out the communists.

The struggle proved particularly sharp in London. In the capital city around half of the CPGBs members were active in their CLPs. And despite claiming that it was the communists who were “splitting the movement”, the bureaucracy strove to do just that. Battersea CLP was disaffiliated because it dared to back Saklatvala and refused to exclude CPGB members. Similar measures were taken against Bethnal Green CLP, where the communist ex-mayor, Joe Vaughan, was held in particularly high regard.

The left in the Labour Party fought back. The National Left Wing Movement was formed in December 1925. Its stated aim was not only to fight the bans on communists, it also sought to hold together disaffiliated CLPs.

The NLWM insisted it had no thought of superceding the Labour Party, but, instead, it sought to advance rank-and-file aspirations. In this the NLWM was considerably boosted by the newly established Sunday Worker. Despite being initiated, funded and edited by the CPGB, the Sunday Workerserved as the authoritative voice of the NLWM. At its height it achieved a circulation of 100,000. The NLWM’s 1925 founding conference had nearly 100 Labour Party organisations sending delegates.

Yet the right’s campaign of disaffiliations and expulsions remorselessly proceeded. The NLWM therefore found itself considerably weakened in terms of official Labour Party structures. Hence at the NLWM’s second annual conference in 1927 there were delegates from only 54 local Labour Parties and other Labour groups (representing a total of 150,000 individual party members). It should be added that militant union leaders, such as the miners’ AJ Cook, also supported the conference.

With the counterrevolution within the revolution in the Soviet Union, the CPGB was in many ways reduced to a slave of Stalin’s foreign policy. The CPGB’s attitude towards the Labour Party correspondingly changed. Leaders such as Harry Pollitt and Rajani Palme Dutt denounced the Labour Party as nothing but “a third capitalist party” (shades of Peter Taaffe and the Socialist Party in England and Wales).

As an integral part of this self-inflicted madness, in 1929 the Sunday Worker was closed and the NLWM wound up. In effect the CPGB returned to its SDF roots. Ralph Miliband regretfully comments that the CPGB’s so-called new line “brought it to the nadir of its influence”. Sectarianism could only but spur on the right’s witch-hunt. In 1930 the Labour Party apparatus produced its first ‘proscribed list’. Members of proscribed organisations became ineligible for individual membership of the Labour Party and CLPs were instructed not to affiliate to proscribed organisations. Needless to say, most of those organisation were closely associated with the CPGB.

However, what began with action directed against the CPGB-led National Unemployed Workers’ Movement and the National Minority Movement has now morphed into the catch-all ban on “racist, abusive or foul language, abuse against women, homophobia or anti-Semitism at meetings, on social media or in any other context”. Nowadays the Labour Party apparatus can, at a whim, expel or suspend anyone.

Surely, beginning with the Liverpool conference, it is time to put an end to the bans and proscriptions. We certainly have within our power the possibility of once again establishing the Labour Party as the united front of all working class organisations in Britain.