Once all working class and socialist organisations were welcome – obviously no longer. James Marshall looks at the past, present and future

We are in the midst of a terrible witch-hunt – a witch-hunt fully backed by the Labour right, the capitalist media, the courts, the Israeli embassy and the forces of the deep state. Three examples:

- Jeremy Corbyn was suspended from membership of the Parliamentary Labour Party in October 2020, thereby preventing him from standing as a Labour candidate in the next general election. Why? He dared tell the truth: “accusations” of anti-Semitism have been “dramatically overstated for political reasons by our opponents inside and outside the party, as well as by much of the media”. Constituency Labour Party chairs and secretaries who allowed debates on, or resolutions protesting against, his treatment faced suspension or expulsion.

- Hundreds, if not thousands, have been purged, many charged with anti-Semitism, and predictably a hugely disproportionate percentage of them are Jewish: eg, Jackie Walker, Tony Greenstein and Moshé Machover. Their real crime is opposing the Zionist colonial-settler state of Israel … and Labour’s pro-capitalist right wing.

- The July 20 national executive committee banned Labour Against the Witchhunt, Resist, the Labour In Exile Network and Socialist Appeal. Anyone deemed a member or supporter of one of those proscribed organisations faces auto-expulsion. Amongst the first to fall foul of the new rule was celebrated film director Ken Loach. He refused to renounce support for LAW.

It is all too clear what Sir Keir Starmer and general secretary David Evans are up to. Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership victory in September 2015 owed much to historical accident; little or nothing to the strategic acumen, ideological hegemony and organisational strength of the official left. With his ill-judged resignation following the December 2019 general election and the resounding defeat suffered by the hapless Rebecca Long-Bailey in the April 2020 leadership contest, the Labour right has been firmly back in the saddle. The witch-hunt is no longer about undermining Corbyn, driving him into complicity, forcing him to sacrifice one friend and one ally after another and ensuring that he never enters No10 Downing Street as prime minister.

No, the witch-hunt is about Sir Keir demonstrating his unquestioning loyalty to the UK state and its international allies – crucially the US and its most important strategic asset in the Middle East. Bans, expulsions, character assassination and riding roughshod over basic democratic norms have a potent symbolic value. They show that Starmer is worthy of the establishment’s trust. That way, he hopes to ingratiate himself with the capitalist media, boost Labour’s poll ratings and calm the fears of the army top brass, MI5, the City and the US state department. If – and it is a big if – Brexit comes to be commonly regarded as a Boris Johnson-driven car crash, then Sir Keir has the distinct possibility of getting that summons to Buckingham Palace and being asked to form a government by her majesty the queen.

Class against class

Labour Party Marxists has actively joined with those many others fighting the suspension and expulsion of socialists, trade union activists and anti-Zionists. All of them, without exception, should be immediately reinstated. There is surely nothing uncontroversial about Marxists making such a demand. After all, what is going on inside the Labour Party is a clear and unmistakable manifestation of the class struggle.

What then should we make of those self-declared ‘leftwingers’ who have turned a blind eye, excused, complied with or even promoted the witch-hunt? Painful though it may be for many, the fact of the matter is that it was under the pro-Corbyn regime of Jennie Formby that Labour HQ ‘fast-tracked’ expulsions. ‘Denialism’ – ie, what Corbyn was charged with – first became a crime with general secretary Formby (denialism, in this context, being a refusal go along with the big lie that Labour has a widespread, politically significant problem with anti-Semitism).

Yet, as the witch-hunt ripped through the ranks of the Labour left, John McDonnell, Diane Abbott and the Socialist Campaign Group of MPs maintained a studied silence. None of them defended Ken Livingstone, Chris Williamson, Pete Willsman or Marc Wadsworth. The principle, ‘An injury to one is an injury to all’, became an alien concept. The Guardian’s house-trained Owen Jones was little different. Nor did Momentum lift a finger. Indeed Jackie Walker was surgically removed as its vice-chair.

Then there is Dan Randall and the social-imperialist Alliance for Workers’ Liberty outfit. They might as well be paid agents of the foreign office. Perhaps, though, the most revolting of all is Robert Griffiths, leader of the Morning Star’s Communist Party of Britain. He actually wrote to the Labour Party’s witch-hunter-in-chief, Iain McNicol, asking him to name the names of any members of his who had entered the Labour Party “or engaged in any similar subterfuge”, so that “action can be taken against them”. Not to leave a shadow of doubt, Griffiths signed off: “With comradely regards”.

Exactly how Griffiths’ sorry excuse for a communist organisation arrived at its ban on Labour Party members joining the CPB and the ban on CPB members joining the Labour Party need not concern us here. Its roots, though, surely lie in the ‘official’ Communist Party of Great Britain and its turn to the cross-class politics of the popular front, sanctioned by the 7th Congress of the Communist International in 1935 under Stalin’s direct command.

Despite CPB claims to be the unbroken continuation of the CPGB going back to its foundation in 1920, nothing could be further from the truth. A fundamental break occurred. The same goes for the Labour Party.

Beginnings

From its beginning Labour was a federal party, which sought to unite all working class and socialist organisations. It was a united front of a special kind – special because, as with the soviets in Russia, unity was not tactical, fleeting or episodic. True, especially at first, political aims were decidedly limited.

JH Holmes, delegate of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, moved this historic resolution at the 1899 TUC:

That this Congress, having regard to its decisions in former years, and with a view to securing better representation of the interests of labour in the House of Commons, hereby instructs the Parliamentary Committee to invite the cooperation of all cooperative, socialistic, trade unions and other working class organisations to jointly cooperate on lines mutually agreed upon, in convening a special congress of representatives from such above-named organisations as may be willing to take part to devise ways and means of securing the return of an increased number of labour members in the next parliament.

His resolution was opposed by the miners’ union on the basis of impracticability, but found support from the dockers, the railway servants and shop assistants. After a long debate the resolution was narrowly carried by 546,000 votes to 434,000.

The TUC’s parliamentary committee oversaw the founding conference of the Labour Representation Committee in February 1900. The 129 delegates, representing around 500,000 members, finally agreed to establish a distinct Labour Party in parliament, with its own whips, policies, finances, etc.

An executive committee was also elected. It would prepare lists of candidates, administer funds and convene an annual conference. Besides affiliated trade unions, the newly formed NEC would also include socialist societies. In fact, they, the socialist societies, were allocated five out of the 12 NEC seats (one for the right-reformist Fabians, two for the centrist Independent Labour Party and two for the openly revolutionary Social Democratic Federation). Given the diminutive size of these socialist societies compared with the trade unions, it is obvious that they were treated with considerable generosity. Presumably their “advanced” views were highly regarded.

For Keir Hardie the formation of the Labour Party marked something of a tactical retreat. He had long sought some kind of socialist party. However, to secure an alliance with the trade unions he and other ILPers were prepared to programmatically limit the Labour Party to nothing more than furthering working class interests by getting “men sympathetic with the aims and demands of the labour movement” into the House of Commons.

SDF delegates proposed that the newly established Labour Party commit itself to the “class war and having as its ultimate object the socialisation of the means of production and exchange” – a formulation rejected by a large majority. In the main the trade unions were still Liberal politically. Unfortunately, as a result of this vote, the next annual conference of the SDF voted by 54 to 14 to withdraw from the Labour Party. Many SDF leaders came to bitterly “regret” this sectarian decision.

As might be expected, this was part of a wider pattern. For example, faced with the great industrial unrest of 1910-14, Henry Hyndman, the SDF’s autocratic leader, rhetorically asked: “Can anything be imagined more foolish, more harmful, more – in the widest sense of the word – unsocial than a strike?”

Of course, it is quite possible to actively support trade unions in their struggles over wages, conditions, etc, and to patiently and steadfastly advocate republican democracy and international socialism. Indeed without doing just that there can be no hope for a mass socialist party here in Britain.

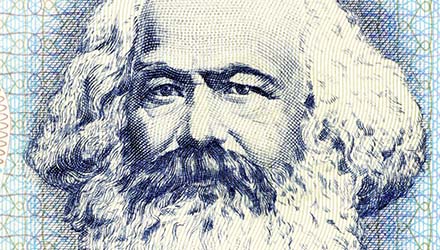

Nonetheless, the SDF is too often casually dismissed by historians. Eg, Henry Pelling describes it as “a rather weedy growth in the political garden”. True, its Marxism was typically crude and, with Hyndman, mixed with more than a tinge of anti-Semitism. For him the Boer war was instigated by “Jew financial cliques and their hangers-on”. Yet the SDF was “the first modern socialist organisation of national importance” in Britain.

Karl Marx disliked it, Fredrick Engels despaired of it, William Morris, John Burns, Tom Mann and Edward Aveling split from it. But the SDF survived. The various breakaways – eg, the Socialist League, the Socialist Party of Great Britain and the Socialist Labour Party – either disappeared, remained utterly impotent or could manage little more than regional influence. Meanwhile, the SDF continued as the “major representative” of what passed for Marxism in this country till 1911, when it merged with a range of local socialist societies to become the British Socialist Party.

The first conference of the newly formed BSP voted, by an overwhelming majority, to “seek direct and independent affiliation” to the Second International. In other words, not through the Labour Party-dominated British section of the Second International. Despite that, however, the BSP began to overcome its Labour-phobia. Leading figures, such as Henry Hyndman, J Hunter Watts and Dan Irving, eventually came round to affiliation. That was vindication for Zelda Kahan and the internationalist left. Withdrawal from the Labour Party, she argued, had been a profound mistake. Outside the Labour Party the BSP was seen as hostile, fault-finding and antagonistic. Inside, the BSP would get a wider hearing and win over the “best” rank-and-file forces. Affiliation to the Labour Party was agreed, albeit by a relatively narrow majority. Efforts then began to put that into effect. The formal application for affiliation was submitted in June 1914. And in 1916 – things having been considerably delayed due to the outbreak of World War I – the BSP gained entry into the Labour Party. Almost simultaneously, in Easter 1916, the BSP in effect expelled the pro-war right wing. Hyndman went off to form his National Socialist Party.

Communist affiliation

The October revolution found militant and unstinting support in the BSP. A number of its émigré comrades from Russia returned home and took up important positions in the Soviet government. Bolshevik publications were soon being translated into English: eg, Lenin’s State and revolution. Money too flowed in.

The Leeds conference of the BSP in 1918 enthusiastically declared its solidarity with the Bolsheviks and a wish to emulate their methods and achievements. And under the influence of Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Bukharin, etc, the BSP adopted a much more active, much more agitational role in the Labour Party and the trade unions. In the words of Fred Shaw, instead of standing aloof from the “existing organisations” of the working class, “win them for Marxism”.

Needless to say, the BSP constituted the main body that went towards the historic formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain over July 31-August 1 1920. Given BSP affiliation four years earlier, and the fact that in 1918 the Labour Party introduced individual membership, there can be no doubt that the bulk of CPGBers were card-carrying Labour Party members. Dual membership was therefore the norm, as with the Fabians and ILP.

However, instead of simply informing Arthur Henderson, Labour’s secretary, that the BSP had changed its name, the CPGB, following Lenin’s advice, applied for affiliation. Lenin thought the CPGB was in a win-win situation. If affiliation was accepted, this would open up the Labour Party rank and file to communist influence. If affiliation was rejected, this would expose Labour leaders for what they really were: “the worst kind of reactionaries”.

With 20:20 foresight it would probably have been better for the CPGB to have presented itself merely as the continuation of the BSP. True, that would have tested to the limits the CPGB’s own unity. Its First Congress had a surprisingly large minority opposed to Labour Party affiliation: eg, the Communist Unity Group.

Nevertheless, securing a divorce is undoubtedly far harder than turning down a would-be suitor. The Labour leadership would have had to expel a renamed existing affiliate rather than reject a brand new prospective affiliate. Note, the BSP was allowed to affiliate in 1916, despite its long established commitment to Marxism, and, as far as I know, there were no moves to expel the BSP because of its newly adopted opposition to the ongoing inter-imperialist war – a position shared, of course, by Keir Hardie, Ramsay MacDonald and the centrist ILP.

After World War I and the 1917 Russian Revolution, however, Labour’s grandees were determined to distance themselves from Bolshevism. The revolution had put terror into the soul of the bourgeoisie. Their system was mortal. In defence of their system of exploitation they reinvented capitalism as ‘democracy’, while the communists, in defence of the isolated Soviet republic, championed ‘dictatorship’. A strategic blunder. A gift. Arthur Henderson therefore replied to the CPGB’s first application for affiliation by counterposing democracy and dictatorship. The principles of the communists do not accord with those of the Labour Party, he flatly declared. To which the CPGB responded by pointing out that:

… it understood the Labour Party to be so catholic in composition and constitution that it could admit to its ranks all sections of the working class movement that accept the broad principle of independent working class political action, at the same time granting them freedom to propagate their own particular views as to the policy the Labour Party should pursue and the tactics it should adopt.

A good many local Labour Parties, particularly in London, forthrightly rejected Henderson’s characterisation of the CPGB as, in effect, mad, bad and dangerous to know. Nonetheless, Labour’s apparatus experienced no difficulty in marshalling crushing majorities. Eg, in June 1921 there was an overwhelming 4,115,000 to 224,000 conference vote against CPGB affiliation.

A minority Labour government was now a real prospect. Towards that end Labour had to be made acceptable to the Liberal Party, the capitalist press, the army high command, the City and George V. Britain and its vast empire of exploitation, pillage and extermination would be safe in Labour hands. That was the essential message that the Labour and trade union bureaucracy wanted to convey by rejecting the CPGB.

Lenin had, in 1908, optimistically called Labour the “first step towards socialism and towards a class policy”. As it was, Labour took one step forward in 1900 and one step back with its support for British imperialism in World War I … and still another step back with its refusal to accept communist affiliation. The united front of the working class was thereby disunited. The Labour Party dishonestly continued to call itself by that name, but in reality Labour was sabotaged as a party going towards socialism and a class policy. It continues, of course, but akin to soviets without Bolsheviks: soviets subordinated to the capitalist state; soviets as a career ladder for colourless, clueless, professional politicians.

Bans and defiance

Not that the CPGB could be easily seen off. Affiliation might have been rejected, but there remained dual membership. In 1922, two CPGB members won parliamentary seats as Labour candidates: JT Walton Newbold (Motherwell and Wishaw) and Shapurji Saklatvala (Battersea North).

Subsequently, Labour’s NEC was forced to temporarily drop its attempt to bar CPGB members from being elected as annual conference delegates. The June 26-29 1923 Labour conference had 36 CPGB members as delegates, “as against six at Edinburgh” the previous year. Incidentally, the 1923 conference once again rejected CPGB affiliation, this time by a narrower 2,880,000 to 366,000 margin.

Nonetheless, the general election in December 1923 saw CPGBers Ellen Wilkinson (Ashton-under-Lyne), Shapurji Saklatvala (Battersea North), M Philips Price (Gloucester), William Paul (Manchester Rusholme) and Joe Vaughan (Bethnal Green SW) stand as official Labour candidates, while Alec Geddes (Greenock) and Aitken Ferguson (Glasgow Kelvingrove) were unofficial Labour candidates, there being no official Labour candidate in either constituency. Walton Newbold (Motherwell) and Willie Gallacher (Dundee) alone stood as CPGB candidates. Despite a considerable increase in the overall communist vote, none were elected.

A ban on CPGB members standing as Labour Party candidates swiftly followed. Yet, though Labour Party organisations were instructed not to support CPGB candidates, this was met with defiance – not the fawning compliance nowadays personified by the miserable Robert Griffiths. In the run-up to the October 1924 general election, Battersea North Labour Party overwhelmingly endorsed Shapurji Saklatvala, Joe Vaughan was unanimously endorsed by Bethnal Green SW CLP and William Paul similarly by the Rusholme CLP executive committee. And Saklatvala was once again elected as an MP.

The 1924 Labour Party conference decision against CPGB members continuing with dual membership was reaffirmed in 1925. And, going further, trade unions were “asked not to nominate communists as delegates to Labour organisations”. In response, in December 1925, the National Left Wing Movement was formed. Its stated aim was not only to oppose bans on communists: it also sought to hold together disaffiliated CLPs. Basically a model which today’s LIEN seeks to emulate.

The NLWM insisted it had no wish or thought of superseding the Labour Party, but, instead, it sought to advance the generally held aspirations of Labour’s leftwing militants. In this it was considerably boosted by the newly established Sunday Worker. Despite being initiated, funded and edited by the CPGB, the Sunday Worker served as the authoritative voice of the NLWM. At its height it achieved a circulation of 100,000. The NLWM’s 1925 founding conference had nearly 100 Labour Party organisations sending delegates.

Following the defeat of the 1926 General Strike, the Labour apparatus and trade union bureaucracy wanted the movement to draw the conclusion that the only way to make progress would be through cooperating with the capitalist class in the national interest – Mondism. As a direct concomitant of this miserable class-collaborationism there was a renewed drive to exclude communists. Yet, despite these assaults on the Labour Party’s founding principles, at the end of 1926 the CPGB could report that 1,544 of its 7,900 members were still individual members of the Labour Party.

The struggle proved particularly sharp in London. In the capital city around half of the CPGB’s membership were active in their CLPs. And despite claiming that it was the communists who were “splitting the movement”, the labour leadership palpably strove to do just that. Battersea CLP was disaffiliated because it dared to back Saklatvala and refused to bar CPGB members. Similar measures were taken against Bethnal Green CLP, where the communist ex-mayor, Joe Vaughan, was held in particularly high regard.

Yet the Labour leadership’s campaign of disaffiliation and expulsion remorselessly ground on. The NLWM therefore found itself considerably weakened in terms of official Labour Party structures. Hence at its second annual conference in 1927 there were delegates from only 54 local Labour Parties and other Labour groups (representing a total of 150,000 individual party members). Militant union leaders, such as the miners’ AJ Cook, supported the conference.

However, external factors came into play – negatively. With the counterrevolution within the revolution in the Soviet Union, the CPGB was, in many ways willingly, reduced to being a slave of Stalin’s foreign policy. The CPGB’s attitude towards the Labour Party correspondingly wildly zigged and zagged. During the so-called ‘third period’ leaders such as Harry Pollitt and Rajani Palme Dutt denounced the Labour Party as nothing but “a third capitalist party” (shades of Peter Taaffe and Hannah Sell and their Socialist Party in England and Wales).

As an integral part of this madness, in 1929 the Sunday Worker was closed down and the NLWM was wound up. In effect the CPGB returned to its SDF roots. Ralph Miliband comments that the CPGB’s so-called new line “brought it to the nadir of its influence”.

Third period left sectarianism could only but spur on the Labour right’s witch-hunt. In 1930 there came the first proscribed list. Members of a whole variety of organisations became ineligible for individual membership of the Labour Party, and CLPs were instructed not to affiliate to proscribed organisations. Needless to say, most of them were associated in some way or another with the CPGB.

Latest round

What began as a witch-hunt against the CPGB in the 1920s nowadays not only includes LAW, LIEN and Socialist Appeal. There is the catch-all ban on “racist, abusive or foul language, abuse against women, homophobia or anti-Semitism at meetings, on social media or in any other context”. The Victoria Street thought-police can, at a whim, expel anyone. Members live in fear. They silence themselves. They keep their heads down. They fret, worry and sometimes experience profound mental distress over nothing more than past Zoom appearances, social media posts, likes and dislikes. Naturally, often they simply despair, and leave in disgust. They scatter to the four winds and turn to social dust.

However, there is a growing fightback. Twelve NEC members have declared the ban on the four proscribed groups “unfair”. The SCG even summed up the courage to organise a statement, signed by 20 Labour MPs and five Labour peers, urging that Ken Loach be reinstated as a member. In a similar fashion a range of groups have united as Defend the Left to oppose the bans and proscriptions – whatever the many political faults and inadequacies, a positive development. Even better, there are those now committed to the “refoundation of Labour as a united front of a special kind open to all socialist and working class organisations” (LAW).

Here a really valuable lesson has been learnt. Yes, comrades, to fight against the witch-hunt we need a clear vision of what we are fighting for. The struggle continues.